“Use your signature strengths and virtues in the service of something much larger than you are.”

Martin Seligman & Positive Psychology

Martin Seligman is a pioneer of Positive Psychology (the term itself was coined by Abraham Maslow), not simply because he has a systematic theory about why happy people are happy, but because he uses the scientific method to explore happiness. Through the use of exhaustive questionnaires, Seligman found that the most satisfied, upbeat people were those who had discovered and exploited their unique combination of “signature strengths,” such as humanity, temperance and persistence. This vision of happiness combines the virtue ethics of Confucius, Mencius and Aristotle with modern psychological theories of motivation. Seligman’s conclusion is that happiness has three dimensions that can be cultivated: the Pleasant Life, the Good Life, and the Meaningful Life.

The Pleasant Life is realised if we learn to savour and appreciate such basic pleasures as companionship, the natural environment and our bodily needs. We can remain pleasantly stuck at this stage or we can go on to experience the Good Life, which is achieved through discovering our unique virtues and strengths, and employing them creatively to enhance our lives. According to modern theories of self-esteem life is only genuinely satisfying if we discover value within ourselves. Yet one of the best ways of discovering this value is by nourishing our unique strengths in contributing to the happiness of our fellow humans. Consequently the final stage is the Meaningful Life, in which we find a deep sense of fulfilment by employing our unique strengths for a purpose greater than ourselves. The genius of Dr. Seligman’s theory is that it reconciles two conflicting views of human happiness, the individualistic approach, which emphasizes that we should take care of ourselves and nurture our own strengths, and the altruistic approach, which tends to downplay individuality and emphasizes sacrifice for the greater purpose.

The very good news is there is quite a number of internal circumstances […] under your voluntary control. If you decide to change them (and be warned that none of these changes come without real effort), your level of happiness is likely to increase lastingly.

(Seligman 2002, p. xiv)

Some detractors have criticized Positive Psychology as being intentionally oblivious to stark realities. And though Seligman ventures into the area of pleasure and gratification through his research in the area of positive emotion, there is much more to his work beyond this. In his study of the Good Life (cultivating strengths and virtues) and the Meaningful Life (developing meaning and purpose), positive psychology seeks to help people acquire the skills to be able to deal with the stuff of life in ever fuller, deeper ways.

Martin Seligman: A Little Background

Born in 1942, Seligman is credited as the father of Positive Psychology and its efforts to scientifically explore human potential. In Authentic Happiness (2002), he explains that his journey towards this new field in psychology started off in a study on learned helplessness in dogs.

During the course of the study, he noticed that, in spite of numerous configurations, some dogs would not quit and did not “learn” helplessness. This intrigued and excited the self-proclaimed pessimist and he drew parallels between dogs and learned helplessness with depression in humans (Seligman 2002, p. 20-23). This shaped his work and he has since become one of the most often-cited psychologists not only in positive psychology but psychology in general.

A significant moment in Seligman’s life was his landmark speech in 1998, at the time of his inauguration as the president of the American Psychological Association (APA) when he declared that psychologists need to study what makes happy people happy! He noted, “The most important thing, the most general thing I learned, was that psychology was half-baked, literally half-baked. We had baked the part about mental illness […] The other side’s unbaked, the side of strength, the side of what we’re good at.” (Address, Lincoln Summit, Sep. 1999.) In many ways, this signaled the opening of a new perspective for the field of psychology.

One of Seligman’s forerunners, Abraham Maslow, helped to call attention to humanistic psychology, which focused on human strengths and potential rather than neuroses and pathologies. Yet, Maslow was an intuitively inspired theorist with little methodologically sound, empirical evidence to support his claims. The next generation of psychologists such as Seligman, Ed Diener, and Mihaly Csiskzenmihalyi are working to scientifically study the effects of positive emotions and the ways in which they affect health, performance, and overall life satisfaction. More importantly for us, their studies have shown that happiness can be taught and learned.

The Three Dimensions of Happiness

[Positive Psychology] takes you through the countryside of pleasure and gratification, up into the high country of strength and virtue, and finally to the peaks of lasting fulfillment: meaning and purpose.

(Seligman 2002, p. 61)

According to Seligman, we can experience

three kinds of happiness:

1) Pleasure and Gratification

2) Embodiment of Strengths and Virtues

3) Meaning and Purpose.

Each kind of happiness is linked to positive emotion but from his quote, you can see that in his mind there is a progression from the first type of happiness of pleasure/gratification to strengths/virtues and finally meaning/purpose.

The Pleasant Life: Past, Present & Future

Seligman provides a mental “toolkit” to achieve what he calls the pleasant life by enabling people to think constructively about the past, gain optimism and hope for the future and, as a result, gain greater happiness in the present.

Dealing with the Past

Among Seligman’s arsenal for combating unhappiness with the past is that which we commonly and curiously find among the wisdom of the ages: gratitude and forgiveness. Seligman refers to American society as a “ventilationist society” that “deem[s] it honest, just and even healthy to express our anger.” He notes that this is often seen in the types of therapy used for issues, problems and challenges. In contrast, Seligman extols the East Asian tendency to quietly deal with difficult situations. He cites studies that find that those who refrain from expressing negative emotions and in turn use different strategies to cope with the stresses of life also tend to be happier (Seligman 2002, p. 69).

Happiness in the Present

After making headway with these strategies for dealing with negative emotions of the past and building hope and optimism for the future, Seligman recommends breaking habituation, savoring experiences and using mindfulness as ways to increase happiness in the present.

Optimism of the Future

When looking to the future, Seligman recommends an outlook of forward leaning hope and optimism.

The Role of Positive Emotion

Many studies have shown that positive emotions are frequently accompanied by fortunate circumstances (e.g., longer life, health, large social networks, etc). For example, one study observed nuns who were, for the most part, leading virtually identical lifestyles. It seemed that the nuns who expressed positive emotions more intensely and more frequently in their daily journals also happened to outlive many of the nuns who clearly did not. Another study used high school yearbook photos of women to see if the ultimate expression of happiness (a smile) might also be used as an indicator as to how satisfied they might be 20 years later. When surveyed, those who were photographed with genuine, “Duchenne” smiles were more likely to find themselves, in their mid-life, married with families and involved in richer social lives.

In short, positive emotions are frequently paired with happy circumstances. And while we might be tempted to assume that happiness causes positive emotions, Seligman wonders, instead, whether positive emotions cause happiness. If so, what does this mean for our life and our happiness?

The Good Life: Embodying the 6 Virtues & Cultivating the 24 Strengths

The strengths and virtues […] function against misfortune and against the psychological disorders, and they may be the key to building resilience.

(Seligman 2002, p. xiv)

Virtues

One notable contribution that Seligman has made for Positive Psychology is his cross-cultural study to create an “authoritative classification and measurement system for the human strengths”. He and Dr. Christopher Peterson, a top expert in the field of hope and optimism, worked to create a classification system that would help psychologists measure positive psychology’s effectiveness. They used good character to measure its efficacy because good character was so consistently and strongly linked to lasting happiness. In order to remain true to their efforts to create a universal classification system, they made a concerted effort to examine and research a wide variety of religious and philosophical texts from all over the world (Seligman 2002, p. 132).

| They were surprised to find 6 particular virtues that were valued in almost every culture, valued in their own right (not just as a means to another end) and are attainable. |

|---|

| 1. Wisdom & Knowledge. |

| 2. Courage |

| 3. Love & Humanity |

| 4. Justice |

| 5. Temperance |

| 6. Spirituality & Transcendence |

Strengths

Seligman clarifies the difference between talents and strengths by defining strengths as moral traits that can be developed, learned, and that take effort. Talents, on the other hand, tend to be inherent and can only be cultivated from what exists rather than what develops through effort (Seligman 2002, p. 134). For example, many people consider musical ability as more or less inherent and can only be strengthened. On the other hand, one can cultivate the strength of patience, which can lead to the virtue of temperance.

Seligman provides a detailed classification of the different virtues as well as a strengths survey that is available on his website: www.authentichappiness.org.

Seligman sees the healthy exercise and development of strengths and virtues as a key to the good life – a life in which one uses one’s “signature strengths every day in the main realms of your life to bring abundant gratification and authentic happiness.” The good life is a place of happiness, good relationships and work, and from this point, Seligman encourages people to go further to seek a meaningful life in the continual quest for happiness (Seligman 2002, p. 161).

The Meaningful Life

Meaning & Flow

Here Seligman states, rather dismally, that there are no shortcuts to happiness. While the pleasant life might bring more positive emotion to one’s life, to foster a deeper more enduring happiness, we need to explore the realm of meaning. Without the application of one’s unique strengths and the development of one’s virtues towards an end bigger than one’s self, one’s potential tends to be whittled away by a mundane, inauthentic, empty pursuit of pleasure.

Seligman expands on the work of his contemporary and colleague, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, in the area of “flow” to explain, in part, what he means by the meaningful life. Investing oneself into creative work creates a greater sense of meaning in life and accordingly, a greater sense of happiness.

Acts of Altruism and Kindness

Seligman goes one step further than Csikszentmihalyi by exploring the experience of flow and the loss of self-consciousness that is involved in acts of altruism and of kindness.

Kindness […] consists in total engagement and in the loss of consciousness

(Seligman 2002, p. 9)

How can we use our strengths and virtues to achieve a meaningful life? One example could be a gifted martial artist who experiences great pleasure in perfecting her skills in karate and winning prizes in tournaments. Yet then she discovers that one autistic child she is teaching shows signs of enormous improvement. This makes her feels so good that she opens a class for children with special needs.

Seeing these children overcome their challenges gives her still greater happiness. Finally, she becomes so absorbed in the happiness of these children that she forgets about her own happiness! This situation enables her to enrich the lives of others while engaging her own strengths and virtues.

Conclusion

- The pleasant life: a life that successfully pursues the positive emotions about the present, past, and future.

- The good life: using your signature strengths to obtain abundant gratification (through activities we like doing) in the main realms of your life.

- The meaningful life: using your signature strengths and virtues in the service of something much larger than you are. (Seligman 2002, p. 249).

- Here Seligman succinctly describes his formula for happiness in life.

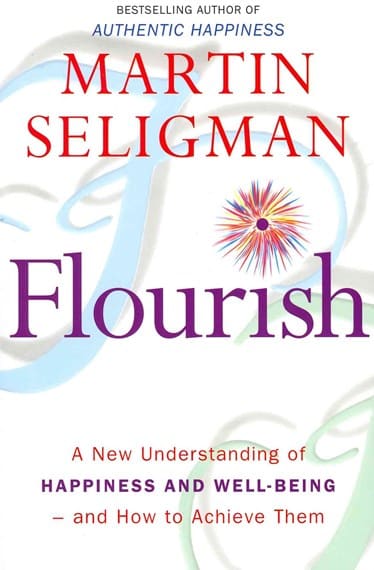

Flourishing

In the introduction to “Flourish,” Seligman presents the PERMA model as a central framework for understanding and achieving human flourishing. He introduces a concept of well-being that extends beyond traditional notions of happiness and discusses the five essential elements that make up PERMA:

1. Positive Emotion: The Foundation of Well-Being

- Seligman delves into the first component of PERMA, Positive Emotion, emphasizing the significance of experiencing joy, gratitude, and other positive emotions in our daily lives. He explains how cultivating positive emotions can be a stepping stone toward a more fulfilling existence.

2. Engagement: The Flow of a Meaningful Life

- Seligman explores the concept of engagement, which involves being fully immersed in activities that provide a sense of flow and absorption. He discusses how engaging in activities that align with one’s strengths and interests can lead to a sense of purpose and well-being.

3. Relationships

- Seligman underscores the importance of positive relationships as a key component of the PERMA model. He explains how nurturing meaningful relationships and building strong social bonds contribute to a flourishing life, emphasizing the role of relationships in enhancing overall well-being.

4. Meaning: Discovering Purpose in Life

- Under this topic, Seligman discusses the significance of finding purpose and meaning in life, exploring how aligning one’s values and aspirations with a sense of purpose can lead to a more fulfilling and meaningful existence.

5. Accomplishment: Striving and Achieving Goals

- Seligman explains how setting and achieving goals that align with one’s values and strengths contribute to a sense of achievement and overall well-being.

Although Flourish echoes key points of his original best seller, Authentic happiness, it broadens the view of wellbeing by introducing the concept and significance of achievement, and arguing that the idea of happiness is not precise enough to capture the complexity of wellbeing.

Our Related Articles

The following three scientists also contributed significantly to science of happiness literature:

External Videos & Recommended Reading

- Martin Seligman Ted talk on positive psychology.

- Martin Seligman’s Learned Optimism is used in an intervention for a depressed elderly patient named Sigmund Freud.

- Seligman, Martin E.P. (1991). Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life. New York, NY: Pocket Books.

Bibliography

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

- Seligman, Martin E.P. (1991). Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life. New York, NY: Pocket Books.

- Seligman, Martin E.P. (1996). The Optimistic Child: Proven Program to Safeguard Children from Depression & Build Lifelong Resilience. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

- Seligman, Martin E.P. (2002). Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Seligman, Martin E.P. (2004). “Can Happiness be Taught?” Daedalus, Spring 2004.

- Seligman, Martin E.P. Doing the Right Thing: Measuring Well Being for Public Policy. International Journal of Wellbeing Vol. 1, No. 1. (2011).