A Little Background

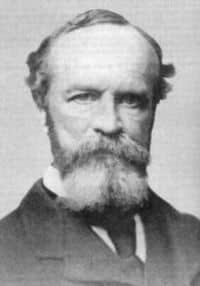

Born in New York in 1842, William James was the oldest of the five children of Henry James Sr., a theologian, and the brother of Henry James, the novelist. The family lived in Europe for five years and returned to the USA, eventually settling in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where James remained for the rest of his life. Unusual for a philosopher, he was happily married and had five children.

James began his career as an art student but soon became interested in science. He entered Harvard Medical School in 1863 and graduated with a doctor of medicine (MD) after six years. His education was interrupted by bouts of illness and depression, which he was able to overcome only by what has been described as a “Promethean act of will.” James was appointed instructor in anatomy and physiology at Harvard, subsequently becoming assistant professor of philosophy, and eventually full professor of philosophy and psychology.

His first major work was Principles of Psychology (1890), which sums up the state of psychology then, and points forward in two directions, to an objective laboratory psychology, and to a phenomenological study of the stream of consciousness. He also discusses the concept of free will, which plays a crucial role in his theory of happiness.

Together with Charles Sanders Peirce, who first coined the term, James founded the philosophical school of pragmatism, which holds that the meaning of an idea is to be sought in its practical effects, that the function of thought is to guide action, and that truth is to be tested by the practical consequences of belief. While this philosophy waned for most of the 20th Century, supplanted by linguistic philosophy, it is currently enjoying a renaissance, and many contemporary philosophers are returning to James as the main inspiration for new theories of perception, meaning, and belief.

The Freedom to Choose

For almost three years after receiving his MD, James lived in his family home battling ill health and depression. He would later describe this depression as a “crisis of meaning” brought on by his studies in science. These left him feeling that there was no ultimate meaning in life, and that his belief in freewill and God were illusions. James suffered panic attacks and hallucinations just like his father before him, which caused him to believe that his illness was rooted in a biological determinism he could not overcome. One day in April of 1870, after reading an essay by Charles Renouvier, his psychological fever began to subside. He had come to believe that freewill was not an illusion and that his own will could alter his psychological state. As he writes in his journal from that time:

I think that yesterday was a crisis in my life. I finished the first part of Renouvier’s second Essais and see no reason why his definition of free will — ‘the sustaining of a thought because I choose to when I might have other thoughts’ — need be the definition of an illusion. At any rate, I will assume for the present — until next year — that it is no illusion. My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will.” (Barton p.323)

As we shall see, this is one of the chief kernels of his theory of happiness—the idea that happiness depends on a choice that we are able to make, regardless of our biological and social circumstances.

James was able to confirm this insight in his later psychological investigations. In his chapter on the will in Principles of Psychology (1890), James argues that voluntary movements are secondary, not primary functions of our organism. In order for me to perform some movement, I must already have a memory of that movement in my mind. This memory arises through the primary, involuntary performances of my organism, such as reflex, instincts, and emotions.

Consider, for example, a newborn infant. The infant is spanked and its instinctive response is to cry. This is a reflex that is beyond the control of the infant, and has not been learned from anyone else. The baby will continue to have involuntary experiences of crying until it develops a memory of crying. Only when this point is reached is the child capable of choosing to cry. Recall the many times you have seen young children crying, pausing from time to time to look around to see what effect their crying is having on bystanders and then starting up again. It is evident that they have learned the involuntary experience of crying instinctively, and now can exercise the ability to cry at will based on that prior involuntary experience.

James concludes that the first time we experience a primary movement we are spectators, as surprised by our behavior as anyone. But once such a movement is in our memory, we can learn to select it at will. Freedom of the will does indeed exist, then, but not as the freedom to create an idea; rather, it is the freedom to attend to and act on one of a number of ideas that have come to us in a way that is beyond our conscious control.

The implications for happiness are clear: while the contents of our consciousness are simply “there” independently of our will, we have the freedom to select which bits of information to focus on, and which bits to reject. A person thus has the ability to direct the flow of the stream of consciousness. Those people who develop this ability are able to exercise more control over their minds, resulting in a deeper sense of empowerment.

Happiness is Created, not Discovered

One difficulty in explaining James’ view of happiness is that he seldom uses the word “happiness,” and when he does he often views it disparagingly, as though it is detrimental to leading an authentic life where the “deepest truths” of one’s existence are revealed. Part of this may be simply an awareness of Bishop Butler’s paradox– that the attempt to be happy is one of the chief sources of unhappiness. Nevertheless, if we identify happiness with “meaningful, fulfilled life” as defined by recent writers on happiness such as Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, I think we can extract a deep and compelling theory from James’ writings.

According to James, happiness is created as a result of our being active participants in the game of life. Instead of brooding on the suffering and evils of existence, we are to readjust our attitudes and act as if life does have an ultimate meaning, even though this can never be proved by the rational mind. As James writes, “Believe that life is worth living, and your very belief will help create the fact.” (Pragmatism and Other Writings, p. 240)

James comes to this conclusion after much reflection on the perennial question “Is Life worth Living?” Some people seem naturally happy and do not need to consciously choose to be happy. But more and more, James suggests, people are losing faith in a meaningful universe and as a result, there is a deep sense of malaise affecting modern society. Partly this is due to the rise of modern science and a decline of faith in traditional religion such as Christianity. Science appears to present to us a world of meaningless actions and reactions with no purpose; and the theory of evolution in particular represents Nature as a war of all struggling against all to survive. It is increasingly difficult to believe in a benevolent Creator overseeing all of this madness.

As a result, it is easy to adopt a pessimistic attitude which in turn fuels depression, anxiety, and other negative states of mind. James writes that pessimism is at root a religious disease, stemming from a “contradiction between phenomena of nature and the craving of the heart to believe that behind nature there is a spirit whose expression nature is.” There are two main strategies to resolve this contradiction and thereby overcome the pessimism. One way is to simply accept the scientific view of the world and actively rebel against the idea of God as Creator or the notion of a spirit behind nature. This move anticipates Camus-style existentialism, where one finds meaning in the heroic and honest affirmation of the inherent absurdity of life.

The other strategy is to resolutely affirm “the existence of an unseen order of some kind in which the riddles of the natural order are explained.” Here, we either have a blind faith in traditional religious answers, or we presume some future state whereby this “unseen world” will be discovered and verified by science. Today we might say that these answers are represented by either fundamentalists who dogmatically assert the ultimate truth of their religious beliefs irrespective of evidence, or New Age thinkers who dogmatically assert that science and religion will ultimately be reconciled at some distant time in the future.

James rejects both these ways of overcoming pessimism. James rejects both belief in the world of the scientist and the “invisible world” invoked by our religious demands as somehow ultimate. Rather he suggests that we trust the idea that “a still wider world may be there” as a “maybe”, “a mere sign or vision” and then act as if the invisible world thereby suggested was real, enabling us to live in the light of our religious demands. Our very risk of acting “as if” there is an ultimate meaning to life will produce a certainty in our hearts that is denied by the rational mind. Once the horizon of one’s life points to something beyond it, one is opened to the possibility of achieving very high states of consciousness that are denied to those who hesitate to act.

James’ view is well expressed by Bruce Springsteen’s popular song, “Reason to Believe.” There is no reason to believe that life has a meaning, but the happiest people are those who go on believing anyway, hoping for a better future. James would add however that it is not mere fantasizing about the future that produces a happy life; it is acting based on this fantasy. At the end of his article “Will to Believe,” James quotes Fitz James-Stephens in support of this idea:

We stand on a mountain pass in the midst of whirling snow and blinding mist, through which we get glimpses now and then of paths which may be deceptive. If we stand still we shall be frozen to death. If we take the wrong road we may be dashed to pieces. We do not certainly know whether there is any right one. What must we do? ‘Be strong, and of good courage.’ Act for the best, hope for the best, and take what comes. If death ends all, we cannot meet death better. (p. 218)

Once Born and Twice Born People

In his book The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), James draws a contrast between two different kinds of people, the “Once Born” and the “Twice Born.” Once Born people are those who seem to be biologically predisposed to happiness: they have a childlike acceptance of life as it is, and they refuse to be bothered by the intense sufferings and evils in the world. James’ example of this is Walt Whitman, and he quotes R.M. Bucke’s description of him:

He never spoke deprecatingly of any nationality or class of men, or time in the world’s history, or against any trades or occupations–not even against any animals, insects, or inanimate things, nor any of the laws of nature, nor any of the results of those laws, such as illness, deformity, and death. He never complained or grumbled either at the weather, pain, illness, or anything else. He never swore. He could not very well, since he never spoke in anger and apparently never was angry. He never exhibited fear, and I do not believe he ever felt it. (p. 84)

However, if you feel there is something inherently wrong with the universe, if you feel that something is terribly amiss with the way things are and must be rectified, then you are twice-born. These are the sick souls of the world, those with a demeanor of natural pessimism:

There are persons whose existence is little more than a series of zigzags, as now one tendency and now another gets the upper hand. Their spirit wars with their flesh, they wish for incompatibles, wayward impulses interrupt their most deliberate plans, and their lives are one long drama of repentance and of effort to repair misdemeanors and mistakes. (p.169)

Based on these definitions, one might think that Once Born people are happy while Twice Born people are unhappy, but in fact James argues that some of the happiest people are actually Twice Born. How is this possible? Well, the Twice Born attitude towards life often leads to a “crisis” expressed by a pathological depression, often accompanied by a strong desire to make sense of things. This positive desire is incompatible with the underlying negative emotional state, producing a contradiction which finds resolution in a transcendence of the negative state into a new, profound sense of the love of life. James could have taken his own “crisis of meaning” event as an example, but instead he discusses Leo Tolstoy. James explains that the Russian novelist’s successful effort to restore himself to mental health led to more than a return to his original condition. The twice-born reach a new and higher plane:

The process is one of redemption, not of mere reversion to natural health, and the sufferer, when saved, is saved by what seems to him a second birth, a deeper kind of conscious being than he could enjoy before. (p.157)

This sense of being “born again” is characteristic of religious and mystical experiences, but it can be extended to any experience where there is a strong sense of renewal after a tragic event. This often happens as a result of a debilitating sickness or a near-death experience. As an example, consider many of the children with terminal cancer at the St. Jude Hospital for Children. Instead of being defeated by their illness, blaming God or the world, they exhibit a tremendous enthusiasm for life and an optimism that “all will be for the best.” The morale of the story is clear: challenges and tragedies can be seen not as obstacles to happiness, but rather as the means to achieve a deeper and more lasting happiness.

Conclusion

From what has been said, we can abstract four main ingredients for a happy life, according to James:

Happiness requires Choice: the world in itself is a neutral flux of “booming blooming confusion,” hence it is entirely up to us whether to view it as positive, negative, or as absent of all meaning.

Happiness requires Active Risk-taking: happiness is not produced merely by thinking or by resigning oneself to life’s circumstances, but rather by taking bold risks and acting on possibilities that come from the “heart’s center,” the Real Self within.

Happiness involves “As-if” thinking: while we cannot prove rationally that freewill exists or that life is meaningful, acting “as if” we are free or “as if” there is an ultimate meaning in life will through that very activity produce a free and meaningful life.

Happiness often comes after a Crisis of Meaning: throughout history, the happiest people often record going through a deep depression caused by a sense of the loss of meaning…these events should not be repudiated but welcomed since only through them is the “Twice-born” sense of renewal possible.

Further Readings

Our articles about the following three researchers may also serve your research:

Bibliography

- Ralph Barton Perry (1996). The Thought and Character of William James. Vanderbilt University Press.

- Barzun, Jacques (2002). A Stroll with William James. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Hunt, Morton (2009). The Story of Psychology. New York: Knopf Doubleday.

- James, William (1890). Principles of Psychology. New York: Henry Holt.

- James, William (1902, 1982) The Varieties of Religious Experience. London: Penguin Books.