Table of Contents

Key Discoveries

People who have one or more close friendships appear to be happier.

The sharing of personal feelings (self-disclosure) plays a major role in the relief of stress and depression.

Listening carefully and responding in encouraging ways (Active-Constructive Responding) is a very effective way to cultivate positive emotions and deepen relationships.

The Scientific Evidence

Our journey to happiness is one we make with companions. One of the most important and rewarding experiences of our lives is the love and friendship we share with those who are dear to us. We most often share positive relationships with our friends, spouses, and other family members, but our circle may also include co-workers, teachers, and anyone else with whom we are in regular contact.

People with “strong ties to friends and family and commitment to spending time with them” have the highest levels of wellbeing”

(Diener & Seligman, 2002).

In 2002, two pioneers of Positive Psychology, Ed Diener and Martin Seligman, conducted a study at the University of Illinois on the 10% of students with the highest scores recorded on a survey of personal happiness. They found that the most salient characteristics shared by students who were very happy and showed the fewest signs of depression were “their strong ties to friends and family and commitment to spending time with them.” The New Wallis, 2005).

In one study, people were asked on random occasions about their mood. They were found to be happiest when they were with their friends, followed by family members, and least happy if they were alone (Larson, et al., 1986). Another study constructed a scale of cooperativeness, i.e., how willing people were to constructively engage in activities with others. This study showed that the cooperativeness of an individual was a predictor of their happiness, though it did not conclusively show if their cooperation resulted in happiness or the other way around (Lu & Argyle, 1991). A study on the quality of relationships found that to avoid loneliness, people needed only one close relationship coupled with a network of other relationships.

To form a close relationship requires a growing amount of “self-disclosure,” or willingness to reveal one’s personal issues and feelings. Without that self-disclosure people with friends still feel lonely (Collins & Miller, 1994; Horesh & Apter, 2006; Jackson, et al., 2000). In fact, a study found that some students who had many friends were still plagued by loneliness, and this seemed to be related to their tendency to talk about impersonal topics, such as sports and pop music, instead of their personal lives. Self disclosure has been shown to positively affect areas of the brain associated with positive emotions and intrinsic rewards (Wang et al., 2014), and may relieve feelings of depression and negative thinking by inducing feelings of safety. In this way, self-disclosure appears to be related to social support – further described below (Zhen et al., 2018). Self-disclosure alone does not increase well-being. Having a good close social network at work and maintaining low marital distress also play a beneficial role in one’s happiness and life satisfaction (Ruesch et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2012). Supportive communication practices and social support also play important roles in well-being.

Good, supportive communication, which includes listening carefully with no other purpose than to understand another, helps establish and strengthen relationships.

Trying to see things from the other person’s perspective and coming to a shared understanding of the world signals caring, respect, and support.

Listening without judgement also signals a willingness to be influenced – thereby making us (and our cherished worldview) vulnerable to influence.

If we demonstrate an openness to change, we make our relationships even stronger.

In addition to good listening, another communication technique is a valuable relationship-builder – active constructive responding. As Martin Seligman described in Flourish (2012), active constructive responding is more than active listening. It involves enthusiastically engaging in the topic or issue raised by your conversation partner. An example Seligman uses to illustrate active constructive responding is: imagine a friend tells you their child received a prestigious award at school. Active listening might include a smile and a congratulatory response. Active constructive responding would also include follow-on questions into the specifics of the competition and the implications of the award.

The follow-up conversation shows your enthusiasm and sharing of your friend’s joy and pride. It also helps your friend re-experience the excitement of the event and is a very effective way to cultivate positive emotions and deepen relationships. (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2016). This specific communication practice can help people to feel more understood. It also increases our satisfaction with social interactions and causes us to view our conversation partners as more socially attractive (Seligman, 2012).

Happiness isn’t only gained from the social support provided to us, we may also increase our well-being by providing social support to others. Brown and colleagues (2003) found that the more support provided to others, the greater the decrease in mortality. Further support for the power of relationships to improve our well-being was shown by Stillman and colleagues (2009) who discovered that loneliness created lower levels of meaning in people’s lives and increased their levels of depression.

Influential Studies on Relationships and Happiness

Brown, S. L., Nesse, R. M., Vinokur, A. D., & Smith, D. M. (2003). Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: Results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychological Science, 14(4), 320–327.

Introduction

Previous research concerning gerontology and social support has demonstrated a strong association between social contact (social support) and health and well-being. However, it remains unclear whether receiving social support can account for the same benefits in health and wellness. For example, a study by Lu and Argyle (1992) demonstrated that individuals may feel guilt and anxiety when depending on other individuals for support. In addition, “feeling like a burden” to others who provide support is correlated with increased suicidal tendencies (Brown et al., 1999). Because social contact is often related to supporting others (or being supported), the advantages of social contact may actually instead be due to the benefits associated with providing support specifically.

- In this investigation, Brown et al. (2003) utilized data from the Changing Lives of Older Couples (CLOC) sample to address two key questions:

- Do the advantages of providing social support account for the benefits of social contact, which are interpreted often as resulting from support received from others?

- Once the provision of support and dependence are both controlled, does receiving support have an impact on mortality? Brown et al. (2003) was identified as a key study because it had an emphasis on providing social support rather than receiving it. It was discovered that providing social support could decrease mortality.

Methods

Participants were recruited from the CLOC study, which is a prospective study of 1,532 individuals from Detroit and the surrounding area. The sample of respondents for this study consisted of 846 married adults. Face-to-face interviews were administered initially as a baseline assessment, and additional measures were administered over 11 months between 1987 and 1988.

Mortality was continually monitored over a five-year period, and various baseline measures were also assessed, including giving instrumental support to others (GISO), providing and receiving emotional support (GESS), and a variety of control variables consisting of demographic, health, and individual difference data. Other aspects of the marital relationship were also assessed, such as equity and marital satisfaction. Out of the original sample, 134 individuals died over the five years of the study.

Results

First, to investigate whether providing instrumental support decreased the risk of mortality, a hierarchical logistic regression procedure was conducted. The results demonstrated that social contact reduced the risk of mortality (p < 0.05); this finding was also echoed in the literature. The risk of mortality was further decreased by GISO (p < 0.001), but was only slightly increased by RISO (p < 0.10).

No single mediator of the relationship between giving support and mortality was identified; however, other studies demonstrate that aiding others increases positive emotion and will increase cardiovascular recovery, thus implicitly promoting health.

Conclusion

This study, which utilizes a longitudinal and prospective design, demonstrates that mortality was significantly reduced for individuals who provided support to friends, relatives, peers, and neighbors. However, receiving support had no further effect on mortality after the giving of support was taken into consideration. This research has strong implications on the appropriate design of clinical interventions that may currently aim to help individuals feel more supported.

Burgoyne, R., & Renwick, R. (2004). Social support and quality of life over time among adults living with HIV in the HAART era. Social Science & Medicine, 58(7), 1353–1366.“ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14759681/

Introduction

This longitudinal study considered stability in perceived social support and the relationship between social support and health-related quality of life in a sample of 41 adult outpatients living with HIV/AIDS (PHA) in Canada. This study marks a shift away from an emphasis on the psychoneuroimmunological effects of stress toward interest in the potential protective effect of social support; however, such causality has yet to be determined.

The purpose of this study was to systematically assess social support stability as well as cross-sectional associations between social support and quality of life for a sample of HIV-positive adults over an extended period of outpatient clinical care in the context of HAART. Social support and quality of life ratings obtained at the time of initial outpatient clinic registration were compared to ratings available at 2- and 4-year follow-ups. The study also examined the predictive potential and causal directionality between social support and quality of life and changes in these factors over time.

This was identified as a key study because it examined perceived social support in participants with HIV/AIDS.

Methods

Participants (N= 41) were PHA outpatients attending a tertiary-care HIV/AIDS ambulatory clinic within a Toronto, Canada teaching hospital in 1997. The sample was 85% male and 15% female (Mage= 38.8 years; range 22-61 years), and disease stages were 29% asymptomatic stage, 32% symptomatic stage, and 39% AIDS stage. Two years (+/- 1 month) after initial measures, participants were approached to complete a follow-up. Data on medical and immune function factors were collected as well. A third wave was conducted 4 years after initial data collection. Biological measures of clinical symptoms were also conducted at the three time points, as symptom burden has been shown to influence quality of life.

Perceived social support was measured using Affectionate support (expressions of love and affection), Positive Social Interaction support (availability of others with whom to share enjoyable time), and Emotional-Informational support (understanding, encouragement, guidance, and information).

Data from the 3 waves were analyzed using a one-way repeated measures ANOVA with corresponding post hoc one-sample paired t-tests. A multivariate regression model was employed to determine the relative effects of clinical status (symptoms, CD4) and social support ratings on physical and mental ratings at the three study points. This method is based on the premise that causal directionality between two variables can be theoretically verified by comparison of relative strength of association between each variable at one point with the other variable at a later point in time.

Results

Analysis of clinical symptoms showed peak immunologic/virologic outcomes at some point close to T2. The increase in mean number of symptoms from T1 to T3 was significant despite a decrease in number of symptoms from T2 to T3. These results suggest an overall increase in symptom burden that is attenuated over time.

Social support showed a slight reduction over time that is not statistically significant. However, a within-group change in the Affection subscale (Friedman test, p< 0.04) reflected a statistically significant T1–T2 reduction (Wilcoxon signed ranks test, p< 0.05) in that particular dimension of social support.

Conclusion

The results of this longitudinal study suggested slight 4-year reductions in social support perceptions and stability in quality of life ratings. Cross-sectional relationships between perceptions of available social support and ratings of quality of life were inconsistent for this sample. The strongest associations were seen at the first follow-up mark, while initial and final time points showed minimal relation.

Relative importance of support at different phases of illness and treatment could explain the predominance of T2 associations. The association between social support and quality of life may have evolved due to increased health-information needs and communication with health providers. Stronger positive associations between social support and quality of life at T2, when the mean number of symptoms reported was 71% greater compared to T1 and 28% greater compared to T3, suggest that perceptions of social support had the potential to mitigate the negative consequences of symptoms and/or side effects on quality of life perceptions at that time.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. (2002). Very Happy People. Psychological Science, 13(1). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11894851/

Introduction

In this study, researchers investigated factors that would theoretically influence high levels of happiness: social relationships, personality, psychopathology, and other variables (religiosity, exercise, etc.). For a variable to be considered for happiness, all of the “happy” individuals should possess this variable. This was identified as a key study because it separated college students into three different happiness groups (high, norm, low) and discovered that the highest happiness group had more satisfying social relations.

Methods

| The participants of this study consisted of 222 college students who agreed to be involved for an entire semester. The participants took questionnaires (Satisfaction With Life Scale, Global self-reported affect balance, Informant affect balance, Daily affect balance) and were then separated into three groups: | ||

| very happy | average | least happy |

| The participants had to fill out daily reports for 51 days. The highest and lowest 10% were set aside and the remaining participants took three more questionnaires (Memory event recall balance, Trait self-description, Interview suicide measure) to refine the assignments of highest, middle, and lowest. The researchers then compared the upper 10% (n=22), average (n=60) and lowest 10% (n=24). | ||

Results

| Very Happy People | scored about a 30 on the life satisfaction scale, 35 being the highest. They had never thought of suicide, could recall more good events than bad, and experienced more positive than negative emotions on a daily basis. |

| spent the least amount of time alone and was rated highest on good relationships. | |

| Unhappy People | experienced and equal amount of positive and negative feelings on a daily basis, and were only somewhat satisfied with their lives. | rated themselves with subpar relations with family and friends. |

| The unhappy group According to the MMPHI both groups scored in the normal range, but the very happy people were more extraverted, and had lower neuroticism, and higher agreeableness. | |

Helsen, M., Vollebergh, W., & Meeus, W. (2000). Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(3), 319–335. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1005147708827

Introduction

It has been proven that a quarter of Dutch adolescents have experienced serious emotional problems (depression, loneliness, low self-esteem, social isolation, and suicidal thoughts). As a child your main source of social support comes from your parents, while as you age it becomes more centered around your peers. Research has shown that support from parents provides a better indicator of positive development than peer support. The current study focused on the shift in social support at adolescence and its effects on psychological well-being.

This was identified as a key study because it examined two types of relationships (friends and family) and the age at which the support switches in importance from one to the other.

Methods

This study used data from the Utrecht Study of Adolescent Development from 1991. The participants consisted of 2589 young individuals in four different age categories: early adolescents (12-14, n = 549), middle adolescents (15-17, n = 798), late adolescents (18-20, n = 645), and post adolescence (21-24, n = 597). The present study focused on questionnaire data examining parental and friends’ support and emotional problems (HGQ, the Centril ladder, Mini-VOEG, and suicidal thoughts).

Results

There was no difference between perceived parental support between boys and girls (X =67:2 and 66.1 respectively). Girls did experience more support from friends (X = 66.7) than boys (X = 56.7). Girls reported having more emotional problems than boys. Parental support was negatively correlated with emotional issues regardless of the support received from friends.

Conclusion

Around the age of 16 there is a shift of support from parents to friends/peers. Parental support was strongly (negatively) related to emotional problems in adolescents. Support from friends was related to well-being only when perceived parental support was apparent.

Krause, N. (2002). Church-Based Social Support and Health in Old-Age: Exploring Variations in Race. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 57 (6): S332 – S347. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.6.S332

Introduction

Krause explored the relationship between church-based support and health. Literature suggests that religious involvement is associated with good health throughout adulthood (e.g., Koenig et al., 2001), and recent studies continue to examine how such protective factors arise from religion. However, one particular domain lacks substantial investigation: the effects of social relationships within the church. This study sought to assess the relationship between religious support and health in late life. with race as a moderating factor.

This was identified as a key study because it observed older adults with religious beliefs and how religion and community social support play a role in well-being.

Methods

Data was extracted from a nationwide survey of 1,126 elderly adults (66 years of age and older). All participants were of the Christian faith, and the final sample included 748 older White people and 752 older Black people. f Frequency of church attendance, congregation cohesiveness, spiritual support, emotional support from church members, connectedness with God, optimism, self-rated health, and race were measured.

Researchers first tested for differential involvement in religion between older Black and White people. Further analyses assessed the differential impact of religion across the two groups.

Findings revealed that on average, older Black people are more deeply invested in their religion than older White people. When compared to older Black people, older White people reported less cohesive congregations (ß = -.103; p < .001), less spiritual support (ß = -.223; p < .001), less emotional support from church members (ß = -.201; p < .001), and less connected to God (ß = -.117; p < .001). Older White adults also indicated lower optimism (ß = -.173; p < .001). Finally, older White Americans did rate subjective health slightly higher than older Black people (ß = -.103; p < .001).

Results

This study provided evidence against the association between religion and health. Data suggest that health-related benefits of church-based support may be primarily associated with the spiritual support provided by other members. Interestingly, results show that older Black adults may derive greater health-related benefits from religion simply because of increased involvement. Although Krause’s work is noteworthy in its examination of older adult social support, one major limitation is the use of self-reported health measures. Future study might consider alternative measures of physical health, as well as examination of type and intimacy of church social support in both groups.

Loscocco, K., & Spitze, G. (1990). Working Conditions, Social Support, and the Well-Being of Female and Male Factory Workers. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 31, 313–327. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136816

Introduction

Work is a major characteristic of life and has the propensity to influence many different facets of an individual’s personality. Many individuals are growing increasingly concerned with the psychosocial facets of work – in particular, the link between work and well-being. The relationship between work and well-being is one that can in turn influence productivity or disease susceptibility (Loscocco & Spitze, 1990).

Loscocco and Spitze note that when compared to full-time female homemakers, the health of employed women compares favorably (p. 313). The paucity of studies concerning gender or women in the relationship between work and well-being may be due to the difficulty of obtaining appropriate samples due to high levels of gender segregation in industrialized countries.

The current investigation measured working conditions and social supports through organizational sources and self-reports.

This was identified as a key study because it analyzed factory working conditions for both male and female employees. It was determined that social support has a direct effect on well-being.

Methods

The data were provided from plants in seven manufacturing industries in Indiana: electrical machinery, chemicals, prefabricated metals, food processing, nonelectrical machinery, transportation equipment, and printing/publishing. Plants were sampled randomly. The response rate was 42%.

To gather information regarding organizational structure and context, interviews took place with plant and personnel managers, and information was collected from company documents. Top managers administered questionnaires to full-time employees at each worksite. The analyses in this study are limited to 2260 nonsupervisory employees, who perform either skilled, semiskilled, or unskilled blue-collar jobs in 27 different plants. Women composed 29% of the sample.

To measure well-being, two dependent variables were used: distress and happiness.

To measure job demands, two variables were used:

(1) the number of overtime hours the participant worked on average per month, and

(2) job strain (the extent to which the worker feels overloaded/overwhelmed).

Job deprivations, rewards, substantive complexity (how long it would take the worker to train someone to do his or her job), autonomy, income, span of control of supervisors, work environment, work social support, co-worker satisfaction, and supervisor support were also all assessed.

The researchers estimated the impact of personal characteristics, work conditions, and work-related social support upon the emotional well-being of both female and male workers. Results were presented separately for men and women.

Then, Loscocco and Spitze assessed the role of workplace social support in either buffering or conditioning the impact of job demands upon well-being. This is was done by regression equations, in which a product term reflects the interaction between a job condition and a measure of social support. Further equations were generated to examine the extent to which social support (from co-workers, supervisors, or company programs) serves as a buffer for the impact of each job condition on mental health.

Results

Distress

The effects of working conditions upon distress did not show significant differences among between the two genders. Job strain was found to increase distress, although working overtime does not increase distress, perhaps because working overtime may be a choice that individuals make . The findings also demonstrated increased distress if employees worked in a physical environment without strong communication; reduced distress was demonstrated when employees had satisfying relationships with their co-workers. In terms of personal characteristics, children were found to increase the distress experienced by women, which is echoed by previous research (McLanahan & Adams, 1987).

Happiness

Job strain was the only job characteristic found to affect men and women differently: specifically, job strain had a stronger negative impact upon women’s happiness levels than on men’s. The findings indicated that happiness among women is just as responsive (if not more responsive) to job conditions as is happiness among men. Overtime did not influence happiness levels. Substantive complexity and span of control were correlated with happiness:; specifically, individuals with more complex jobs and less close supervision were happier. Social support also exerted a direct effect on well-being among both men and women. Education had a negative effect on women’s happiness, but had no effect on the happiness of men.Conclusion

The results demonstrated that social support in the workplace exerts a direct effect on well-being. There were no significant gender differences in the effects of working conditions upon distress or happiness.

Rüesch, P., Graf, J., Meyer, P. C., Rössler, W., & Hell, D. (2004). Occupation, social support, and quality of life in persons with schizophrenic or affective disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(9), 686–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-004-0812-y

Introduction

Work is a key facet of human life and is responsible for providing a social position, identity, and income. Despite the consensus regarding work’s positive relation to mental health, the World Health Organization estimates that 90% of individuals with a serious psychiatric background are unemployed (Harnois, 2000). Individuals who are mentally ill often indicate that they are dissatisfied about being unemployed. In a study of psychiatric inpatients, most chronic schizophrenia patients reported that a good quality of life would be constituted by social relationships and employment (Angermeyer et al., 1999).

Unemployment does not solely affect income and independence, but also one’s quality of life, which can be considered subjectively (i.e. physical, psychological, and social well-being) or objectively (i.e. broader conditions of living).

This investigation examined the relationship between work status/work objective and subjective quality of life among individuals with severe mental illness (SMI). Three main research questions were studied: (1) In what type of work (competitive employment, minimal work, sheltered work, etc.) are people with severe mental illness engaged? (2) After controlling for mental illness, is an individual’s occupation related to subjective quality of life? (3) To what extent is the relationship between occupation and subjective quality of life mediated by objective quality of life, in terms of economic conditions and social network?

This was identified as a key study because it examined the relationship between work and life satisfaction in a sample of individuals with severe mental illness and it was determined that social support played a large role.

Methods

The present study was executed between January 2000 and March 2001 in the inpatient wards of two Swiss mental hospitals . To participate in the study, the inclusion criteria were: being between the ages of 20 and 50 years, having a main diagnosis of schizophrenic or delusional disorder (or affective disorder), and knowing the German language sufficiently. The sample was composed of 261 inpatients (102 women and 159 men). In terms of psychiatric diagnosis, 158 inpatients suffered from schizophrenia, schizotypal, or delusional disorders, and 103 subjects had a diagnosis of an affective disorder.

Subjective quality of life, was examined in four domains: physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships, and the environment. Social support, objective quality of life (housing, main source of living, and income), and the occupational situation of participants were also assessed.

Chi-square tests and ANCOVA were utilized for exploratory analysis, and the four quality of life scales were significantly intercorrelated. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) with latent variables was used to perform further statistical analysis.

Results

Approximately half of the participants had worked in paid employment in the competitive labor market as a main occupation for the previous year. Thirteen percent of subjects (n=31) had been employed in a “sheltered” workplace. Sixteen percent (n=43) had been involved in unpaid activities similar to “work,” such as education, caring for children, housework, etc. Twenty-five percent of subjects had no occupation.

In this study, many different illness-related variables were assessed, including age onset of the disorder, age at first psychiatric hospitalization, number of psychiatric admissions, days hospitalized in the previous year, psychopathological symptoms, or diagnosis. One-way ANOVAs were conducted, using the type of occupation as the independent variable and the illness characteristics as the dependent variable. The findings demonstrated that the type of occupation was significantly correlated with treatment variables (such as number of psychiatric admissions during lifetime). Specifically: competitive employment (as opposed to sheltered work) and number of admissions last year (F = 3.2; p = 0.025); competitive employment (versus no occupation) and days hospitalized last year (F = 9.8, p < 0.001); competitive employment and unpaid work (versus no occupation). Diagnosis was also found to be related to occupation (X2 =14.1; p = 0.003). Inpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia or delusional disorder were over-represented in “sheltered” workplaces. In contrast, a greater number of inpatients diagnosed with an affective disorder were found to be engaged in unpaid work.

The type of occupation is significantly related to objective quality of life variables, including housing, living, income, and social network. Most participants (75%) that had competitive employment reported that they supported themselves on their own income; other subjects were supported by welfare or by a partner. In terms of social network, except for partner relationships, the frequency of relationships was linked to occupational status. Thus, subjects with competitive employment had the greatest number of frequent, regular contacts with other individuals (friends, coworkers, relatives).

In terms of the subjective quality of life, occupation was linked to three out of the four specific “domains” of subjective quality of life: physical well-being, social relationships, and environment. This relationship remained constant even upon controlling for illness variables . Participants with competitive employment, as well as individuals in unpaid work, were found to have stronger reports of subjective quality of life when compared to individuals without any occupation. Even those with unpaid work were more satisfied with their physical well-being than those without an occupation. For psychiatric inpatients, having no work-like occupation was substantially (negatively) related to the “Living” domain as well as “Social Support.” Social support positively influenced subjective quality of life, satisfaction with health, and satisfaction with social ties. The model also indicated that occupation was significantly linked to only one latent variable of subjective quality of life – social ties, demonstrating that occupation exerts an indirect effect upon inpatients’ satisfaction with social ties.

Conclusion

This study showed that having a work-like occupation is important for the quality of life experienced by psychiatric inpatients . The relationship between work occupation and quality of life is particularly true in terms of social network, social support, and life satisfaction.

Noted Limitations and Future Directions

The authors noted that one key limitation in this study was that it utilized a cross-sectional and naturalistic design, so the correlations between occupation and social network/social support should be only viewed as “causal” with limitations. In addition, some participants in this study reported breaks in their working life during the working period that was assessed (the previous year). The work history, rather than the main occupation, could have influenced quality of life.

Smith, D. A., Breiding, M. J., & Papp, L. M. (2012). Depressive moods and marital happiness: Within-person synchrony, moderators, and meaning. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(3), 338–347.

Introduction

Marital issues can play a huge role in depression. A study done by the Epidemiological Catchment Area reported that out of their sample of maritally distressed women, 45.5% had depression. A study done by O’Leary et al. found that newlyweds’ depression increased 10-fold[? compared to what?]. There are several moderators that can contribute to marital distress and depression. This study focused on three of these: sociotropy vs autonomy, excessive reassurance-seeking, and avoidant and anxious attachment. Sociotropic people were found to be susceptible to depression while autonomous people were less susceptible. Individuals who tend to need excessive reassurance are more often depressed than people who do not need that reassurance. An insecure attachment (avoidant and anxious) style has been associated with marital distress.

This was identified as a key study because it examined how marital distress affects depression. The higher the marital distress, the higher the depression

Methods

This study consisted of 55 married women, 24 of whom were newlyweds . The study examined sociotropy and autonomy (PSI-II), reassurance seeking (DIRI), avoidant and anxious attachment, marital adjustment (DAS), daily depressive mood, (PANAS), and marital happiness (MHS).

Conclusion

Greater marital distress was associated with greater depressive symptoms. Marital distress and depressive symptoms were strongly correlated. The distressed group had more depressive symptoms, were married longer, less maritally satisfied, and had children.

Noted Limitations and Future Directions:

A weakness the researchers noted was that only wives were studied for this project. They also did not have any behavioral assessments and all the associations were congruent. The researchers suggest future longitudinal studies on marriage and depression to examine more associations between them.

Stillman, T. F., Baumeister, R. F., Lambert, N. M., Crescioni, A. W., DeWall, C. N., & Fincham, F. D. (2009). Alone and without purpose: Life loses meaning following social exclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 686–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.007

Introduction

Life’s meaning is not solely dependent on social relationships. However, social interactions play a large part in the evolutionary mechanics of the human population. This study investigated the idea that social exclusion is the cause of a global decrease in self-declared meaningful life.

This was identified as a key study because it examined how being socially rejected and ignored would affect happiness and perceptions of meaningfulness in life.

Methods & Results

This experiment consisted of four studies.

Study 1 |

Methods |

|---|---|

| The first study consisted of 108 undergraduates (75% female). Researchers told the participants that they would be coupled with another participant of the same gender and that they would get to meet after they made a video about their career aspirations. In the laboratory the participants would watch a video by their partner and would make a response video. The experimenter left the room to supposedly give the video to the partner. The experimenter would return with one of three answers classifying the participants into a group. They were either rejected, their partner had to leave (control), or their partner accepted their video. All the participants were given a questionnaire to assess their level of meaningfulness after receiving this information. | |

Study 1 |

Results |

| Rejected participants rated life as less meaningful (M=6.26; SD=.71) than did accepted participants (M= 6.54; SD=.57), F(1,105)=4.32, p=.04; d=.43. Likewise, meaning scores were lower for rejected participants then control participants (M=6.62; SD=.46), F(1,105)=5.65; p=.02; d =.60. | |

Study 2 |

Methods |

| The second study was a recreation of the first study but instead of videos for social acceptance, the participants would play an electronic tossing game with their prospective partner. | |

Study 2 |

Results |

| Like the first study, rejected participants rated life as less meaningful (M=6.26; SD=.71) than did accepted participants (M= 6.54; SD=.57), F(1,105)=4.32, p=.04; d=.43. Likewise, meaning scores were lower for rejected participants then control participants (M=6.62; SD=.46), F(1,105)=5.65; p=.02; d =.60. | |

Study 3 |

Methods |

| Consisted of 202 undergraduate participants. The students were asked to complete a questionnaire at their leisure. The dependent variable was meaningfulnes. The independent variables tested were social exclusion, depression, happiness, optimism, and mood . | |

Study 3 |

Results |

| Loneliness predicted the presence of meaning, r =−.35; p<.001, such that more loneliness was associated with less meaning. Other variables were related to meaningfulness, which were: depression (r =−.24, p=.001), happiness (r =.36, p<.001), optimism (r =.21, p=.003), and mood valence (r =.30, p<.001). | |

Study 4 |

Methods |

| The fourth study was similar to the third. There were 212 undergraduate participants. The students completed a questionnaire with the dependent variable meaningfulness and the independent variable social exclusion. The researchers measured purpose, value, efficacy, and self-worth. | |

Study 4 |

Results |

| Higher levels of loneliness were positively correlated to lower levels of meaning. | |

Conclusions

Social exclusion caused a reduced in the perception of life as meaningful. Loneliness and rejection were associated with low meaning. Social exclusion reduced purpose, value, efficacy, and optimism.

Zimmerman, A., and Easterlin R. (2006). Happily Ever After? Cohabitation, Marriage, Divorces, and Happiness in Germany. Population and Development Review 32(3): 511-528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2006.00135.x

Introduction

Marriage may have a positive and lasting effect on well-being; however, the longevity of such gains is unclear. In a study spanning fifteen years, psychologists argued the “setpoint theory,” stating that “people adapt quickly and completely to marriage” because marital partners return fairly quickly to their happiness level determined by their personality traits and genetics (Lucas et al., 2003).

Zimmerman and Easterlin reconsidered the same data set analyzed by Lucas, et al. (2003) and included additional data. The sample was, of first marriages among previously unmarried people, and data reflected life satisfaction two years prior to marriage and at least two years after marriage. Post-marriage data was crucial in examining whether there is a return to baseline satisfaction after the “honeymoon period,” as some research suggests (Lucas et al., 2003). This study also considered the effects of subjective well-being on the formation of cohabiting unions prior to marriage.

Two key results of the Lucas et al. study were reconsidered: Whether individuals still married two or more years into their first marriage exhibited a return to baseline life satisfaction, and whether a significant increase in life satisfaction occurred around the formation of unions (e.g. cohabitation, marriage).

This was identified as a key study because it is the longest-running panel to study subjective well-being.

Methods

A hierarchical regression model was used to examine life satisfaction of married couples over time. Average life satisfaction of the participants prior to marriage formed the baseline. The study then measured the average difference in life satisfaction from one’s baseline value to after cohabitation. It then measured the average difference in life satisfaction in the first year of marriage (t0) and the next year (t+1) versus one’s baseline value, and the average difference in life satisfaction from the second year of marriage and all years thereafter (t+2 and on) versus one’s baseline value. Finally, the researchers measured the difference in life satisfaction from baseline values in individuals who divorced after two or more years of marriage.

Results

The baseline value of life satisfaction in this sample (0.10) did not differ significantly from that of the German population as a whole. As in previous studies, formation of cohabiting unions prior to marriage raised life satisfaction significantly from baseline values (0.183). During the first year of marriage, life satisfaction increased to a value of .369 above the baseline satisfaction level, but ratings declined to a value of 0.173 above baseline after the first year of marriage. These results confirmed the “honeymoon period” effect on life satisfaction, followed by decline, presumably due to habituation. Nevertheless, married individuals were still happier, on average, then they were in their baseline period.

Findings suggest that the formation of successful unions – cohabiting or marital – positively affects well-being, with no significant difference based on the type of union. Individuals who remain married for two or more years do not revert to their baseline value of life satisfaction, thus contradicting the “setpoint theory.”

Conclusion

This study represents the longest-running panel study to date that includes a measure of subjective well-being. Results suggest that the formation of unions has a significant positive effect on life satisfaction, while the dissolution of unions through separation or divorce has a significant negative effect. These results are consistent with the “social support” interpretation commonly offered for the association between marriage and life satisfaction. Ratings of life satisfaction during cohabitation and two years into marriage did not differ significantly.

Bibliography

To read a comprehensive review of each key study, simply click on each study’s citation:

RELATIONSHIPS: THE CONSTRUCT

Social Support in Relation to Job and Family

Adams, G. A., King, L. A., & King, D. W. (1996). Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work–family conflict with job and life satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 411..

Booth, A. L., & Van Ours, J. C. (2008).Job satisfaction and family happiness: The part-time work puzzle*. The Economic Journal, 118(526), F77–F99.

Cameron, A., Kraus, M. W., Galinsky, A. D., & Keltner, D. (2012). The Local-Ladder Effect: Social Status and Subjective Well-Being. Psychological Science. 23(7), 764-771.

Caprariello, P. A. & Reis, H. T. (2013). To do, to have, or to share? Valuing experiences over material possessions depends on the involvement of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,.104(2), 199-215. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0030953

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310-157. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Ernst Kossek, E., & Ozeki, C. (1998). Work–family conflict, policies, and the job–life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior–human resources research. Journal of aApplied pPsychology, 83(2), 139-149.

Greenhaus, J. H., Collins, K. M., & Shaw, J. D. (2003). The relation between work–family balance and quality of life. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(3), 510–531. doi:10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00042-8.

Loscocco, K., & Spitze, G. (1991). Working Conditions, Social Support, and the Well-Being of Female and Male Factory Worker. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 31, 313–327.

Park, N. & Peterson, C. (2006). Character Strengths and Happiness among Young Children: Content Analysis of Parental Descriptions. Journal of Happiness Studies,. 7(3), 323–341. doi: 10.1007/s10902-005-3648-6

Ryan, R. M., Bernstein, J. H., & Brown W. K. (2010). Weekends, Work, and Well-Being: Psychological Need Satisfactions and Day of the Week Effects on Mood, Vitality, and Physical Symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. Vol. 29(1), 95-122. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.1.95

Rüesch, P., Graf, J., Meyer, P. C., Rössler, W., & Hell, D. (2004). Occupation, social support and quality of life in persons with schizophrenic or affective disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(9), 686–694. doi:10.1007/s00127-004-0812-y

Culture and Social Support

Chan, Y. K., & Lee, R. P. L. (2006). Network Size, Social Support and Happiness in Later Life: A Comparative Study of Beijing and Hong Kong. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7(1), 87–112. doi:10.1007/s10902-005-1915-1

Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., & Taylor, S. E. (2008). Culture and social support. American Psychologist, 63(6), 518–526. doi:10.1037/0003-066X

Lu, L. & Argyle, M. (1991). Happiness and Cooperation. Personality and Individual Differences, 12(10), 1019-1030.

Lu, L., & Gilmour, R. (2004). Culture and conceptions of happiness: Individual oriented and social oriented SWB. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(3), 269–291.

Uchida, Y., Norasakkunkit, V., & Kitayama, S. (2004). Cultural constructions of happiness: Theory and empirical evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(3), 223–239.

Social Support and Health

Anderson, C., Kraus, M. K., Galinsky, A. D., & Keltner, D. (2012). The Local-Ladder Effect: Social Status and Subjective Well-Being. Psychological Science,. 23(7), 764-771.

Blixen, C. E., & Kippes, C. (1999). Depression, social support, and quality of life in older adults with osteoarthritis. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 31(3), 221–226.

Burgoyne, R., & Renwick, R. (2004).

Social support and quality of life over time among adults living with HIV in the HAART era. Social Science & Medicine, 58(7), 1353–1366. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00314-9

Cramm, J. M., Hartgerink, J. M., de Vreede, P. L., Bakker, T. J., Steyerberg, E. W., Mackenbach, J. P., & Nieboer, A. P. (2012).

The relationship between older adults’ self-management abilities, well-being and depression. European Journal of Ageing,. 9(4), 353-360.

Edmondson, Olivia, J. H. & MacLeod, A. K. (2015).

Psychological Well-Being and Anticipated Positive Personal Events: Their Relationship to Depression. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy,. 22, 418–425. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1911

Helgeson, V. S. (2003).

Social support and quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 12(1), 25–31.

Karademas, E. C. (2006).

Self-efficacy, social support and well-being: The mediating role of optimism. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(6), 1281–1290. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.10.019

Lakey, B. & Oreheck, E. (2011).

Relational regulation theory: A new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychological Review,. 118(3), 482-495. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0023477

Linares, L., Jauregui, P., Herrero-Fernandez, D., & Estevez, A. (2016).

Mediationg Role of Mindfulness as a Trait Between Attachment Styles and Depressive Symptoms. Journal of Interdisciplinary and Applied Psychology. 50, 881-896.

Macaskill, A. (2012).

A feasibility study of psychological strengths and well-being assessment in individuals living with recurrent depression. The Journal of Positive Psychology,. 7(5) 372-386.

Newsom, J. T., & Schulz, R. (1996).

Social support as a mediator in the relation between functional status and quality of life in older adults. Psychology and Aging, 11(1), 34. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.11.1.34

Seligman, M. E. (2012).

Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster. https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Flourish/Martin-E-P-Seligman/9781439190760

Street, H., Nathan, P., Durkin, K., Morling, J., Dzahari, M. A., Carson, J., & Durkin, E. (2009).

Understanding the relationships between wellbeing, goal-setting and depression in children. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry,. 38(3),155-161. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01317.x

Turner, J. (1981).Social Support as a Contingency in Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22(4), 357–367.

Lack of Social Support

Cheng, H., & Furnham, A. (2002).Personality, peer relations, and self-confidence as predictors of happiness and loneliness. Journal of Adolescence, 25(3), 327–339.

Jackson, T., Soderlind, A. & Weiss, K. E. (2000).Personality traits and quality of relationships as predictors of future loneliness among American college students. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 28(5), 463-470(8).

Newall, N. E. G., Chipperfield, J. G., Bailis, D. S., & Stewart, T. L. (2013). Consequences of loneliness on physical activity and mortality in older adults and the power of positive emotions. Health Psychology, 32(8), 921–924. doi:10.1037/a0029413

Orth-Gomér, K., Rosengren, A., & Wilhelmsen, L. (1993).Lack of social support and incidence of coronary heart disease in middle-aged Swedish men. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55(1), 37–43.

Marital Satisfaction

Frech, A., & Williams, K. (2007).Depression and the Psychological Benefits of Entering Marriage. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,. 48(2), 149-163. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800204

Smith, D. A., Breiding, M. J., & Papp, L. M. (2012). Depressive moods and marital happiness: Within-person synchrony, moderators, and meaning. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(3), 338–347. doi:10.1037/a0028404

Stack, S., & Eshleman, J. R. (1998).Marital status and happiness: A 17-nation study. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60(2) 527–536.

Friends and Family

Brown, S. L., Nesse, R. M., Vinokur, A. D., & Smith, D. M. (2003). Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: Results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychological Science, 14(4), 320–327. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.14461

Collins, N. L., & Miller, L. C. (1994). Self-disclosure and liking: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 457-475. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7809308

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. (2002).Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1). doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00415

Fowler, J. H., & Christakis, N. A. (2008). Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart Study. BMJ, 337(dec04 2), a2338–a2338. doi:10.1136/bmj.a2338

Helsen, M., Vollebergh, W., & Meeus, W. (2000). Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(3), 319–335.

Kim, J., & Lee, J.-E. R. (2011). The Facebook paths to happiness: Effects of the number of Facebook friends and self-presentation on subjective well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(6), 359–364. doi:10.1089/cyber.2010.0374

Krause, N. (2002). Church-based social support and health in old age exploring variations by race. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(6), S332–S347.

Larsen, R., Mannell, R., & Zuzanek, J. (1986). Daily well-being of older adults with friends and family. Psychology and Aging 1(2), 117-126. doi:10.1037/0992-7974.1.2.117

Powdthavee, N. (2008).Putting a price tag on friends, relatives, and neighbours: Using surveys of life satisfaction to value social relationships. Journal of Socio-economics, 37(4), 1459–1480.

Social Media Use and Wellbeing

Akın, A1. (2012).The relationships between Internet addiction, subjective vitality, and subjective happiness. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking,. 15(8), 404-410. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2011.0609.

Lin, L. Y., Sidani, J. E., Shensa, A., Radovic, A., Miller E., Colditz, J. B., … & Primack, B. A. (2016). Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults. Depression and Anxiety,. 33, 323-–331. doi: 10.1002/da.22466

Nabi, L R., Prestin, A., & So, J. (2013). Facebook Friends with (Health) Benefits? Exploring Social Network Site Use and Perceptions of Social Support, Stress, and Well-Being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, And Social Networking,. 16(10), 721-727. DOIdoi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0521

Seabrook, E. M., Kern, M. L., and Rickard, N. S. (2016). Social Networking Sites, Depression, and Anxiety: A Systematic Review. JMIR Ment Health 3(4): e50. DOIdoi:10.2196/mental.5842

Litwin, H. & Shiovitz-Ezra, S. (2011).Social network type and subjective well-being in a national sample of older Americans. Gerontologist,. 51(3):379-388. https://academic.oup.com/gerontologist/article/51/3/379/559125

General Construct

Lakey, B., & Orehek, E. (2011).Relational regulation theory: A new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychological Review,. 118(3), 482-495.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803–855. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803

Myers, D. G., & Diener, E. (1995).Who is happy? Psychological science, 6(1), 10–19.

Niederkrotenthaler, T., Gould, M., Sonneck G., Stack, S. & Till, B. (2016). Predictors of psychological improvement on non-professional suicide message boards: Content analysis. Psychological Medicine, 46(16), 3429-3442. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27654957/

Nistor, A. A. (2011).b Developments on the Happiness Issue: a Review of the Research on Subjective Well-

being and Flow. Scientific Journal of Humanistic Studies, 3(4), 58-66.

McNulty, J. K., & Fincham, F. D. (2012). Beyond positive psychology? Toward a contextual view of psychological processes and well-being. American Psychologist, 67(2), 101-110. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024572

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF RELATIONSHIPS

Self-Disclosure

Wang, S., Wei, D. T., Li, W. F., Li, H., Wang, K. C., Xue, S., Zhang, Q., & Qiu, J. (2014). A voxel-based morphometry study of regional gray and white matter correlate of self-disclosure. Social Neuroscience, 9(5), 495-503.

Zhen, R., Quan, L., & Zhou, X. (2018). How does social support relieve depression among flood victims? The contribution of feelings of safety, self-disclosure, and negative cognition. Journal of Affective Disorders, 229, 186-192. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29324365

Lack of Social Support

Stillman, T. F., Baumeister, R. F., Lambert, N. M., Crescioni, A. W., DeWall, C. N., & Fincham, F. D. (2009). Alone and without purpose: Life loses meaning following social exclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 686–694. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.007

Friends and Family

Abbey, A., Abramis, D. J., & Caplan, R. D. (1985). Effects of different sources of social support and social conflict on emotional well-being. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 6(2), 111–129. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp0602_2

Joireman, J. A., Lasane, T. P., Bennett, J., Richards, D., & Solaimani, S. (2001). Integrating social value orientation and the consideration of future consequences within the extended norm activation model of proenvironmental behaviour. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 133-155. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164731

Klien, D. A.,; Goldenring, M. J., & Adelman W. P. (2014).HEADDS 3.0: The psychosocial interview for adolescents updated for a new century fueled by media. Contemporary Pediatrics.

.

Relationships: Practical Tips

MAKING FRIENDS: |

||

| According to many experts, including Robert Putnam, the celebrated author of Bowling Alone, close friendships are becoming rarer. Social bonds, the hidden glue that binds our communities, are becoming weaker. It is perhaps no coincidence that a depression epidemic is now sweeping the industrialized world. We are becoming too busy, too hooked up to electronic gizmos, or too self absorbed, to make or keep friends. So how can we make new friends? Or form deeper friendships? | ||

FINDING HAPPINESS THROUGH FRIENDSHIP: |

||

| According to a ton of scientific evidence, friendships and family relationships are some of the greatest sources of happiness. | ||

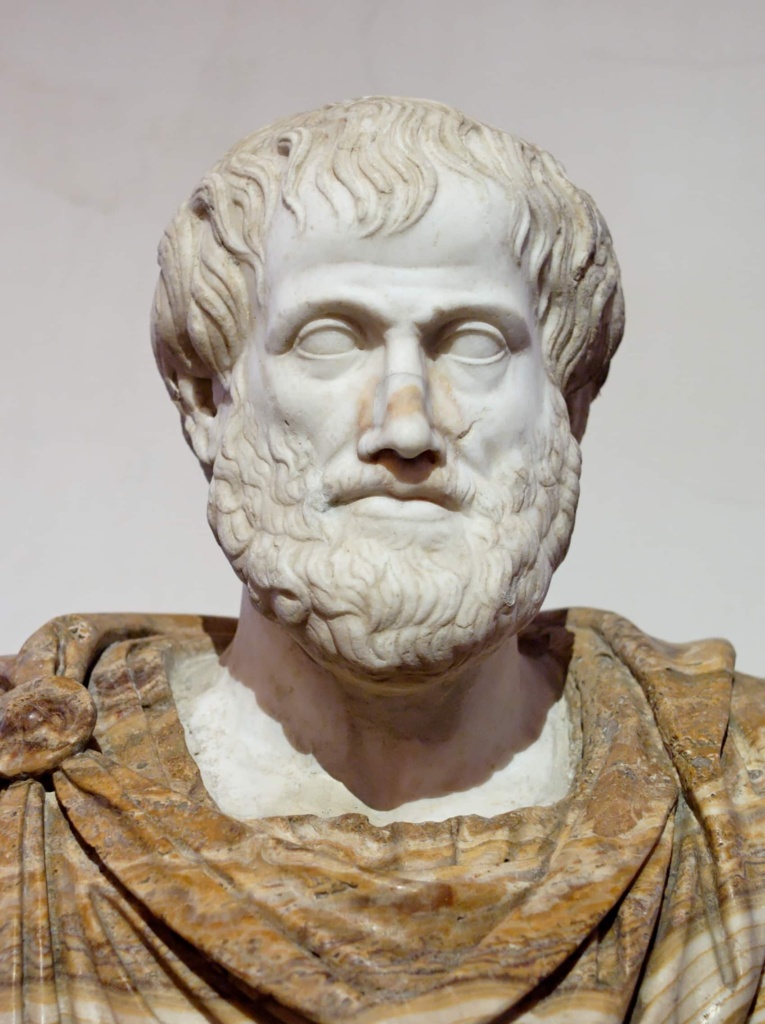

| The great philosophical and political thinker Aristotle split friendships into three types, based on the motive for forming them: | ||

| friendships of utility | friendships of pleasure | friendships of the good. |

| Modern psychology is coming to the same conclusion: Friendships based on unconditional love, ( friendships of the good) have a powerful effect on the well being of both parties. | ||

| It’s OK if your friendship is still stuck in stage one or two, ie “I’ll buy you lunch if you give me a hand with my homework (stage one, utility) and “Let’s hang out. You seem so popular and you make me laugh. ” (stage two, pleasure). But stage three (I love you because you are who you are. I trust you and will stick with you through thick and thin) is way more fulfilling. That sort of relationship simply leaves you feeling great. Aristotle thought the third kind of friendship could take years to build, after you waded through stages one and two. It could still include utility and pleasure, but the driving force was unconditional love. | ||

| Friendships based on utility usually don’t last long because they disintegrate once the “usefulness” of a friend is no longer needed (the genius who got you an A in math was a little boring and liked expensive meals). | ||

| Friendships based on pleasure can last longer, but total trust is still lacking, and if you get into trouble or run out of jokes the “friend” could easily walk away. | ||

| Some people are lucky enough, or loving enough, to transcend utility and pleasure (though these benefits are often still enjoyed) and walk straight into close encounters of the third kind. But according to Aristotle these relationships can take years. They usually take a lot of “work,” ie mutual sacrifice and the significant self control needed not to divulge secrets and break trust. And yet the “payoff” is huge. These “friendships of the good” or “virtuous friendships” fill us with a deeper sense of happiness as we realize that someone loves us for who we are, not for what we do, and will stick around no matter how poor or ugly we get. | ||

| In conclusion, it’s not complicated. Close friendships don’t come free. But we can cut corners. One of the short cuts to genuine friendship is plain old kindness, which leads to the next “habit of happy people,” caring. | ||

Relationships and Happiness:

Parallels Between Modern Science and Ancient wisdom

Confucius hints at the intimate relation between friendship and happiness in the opening lines of the Analects, the earliest record of his sayings:

Isn’t a pleasure to study (the Way) and, on the right occasion, practice what one learns? Isn’t it a delight to meet a friend from afar?

Confucius.

The two thoughts here are interconnected: meeting a friend gives one the opportunity to discuss the Way, and studying the Way is best accomplished in the presence of someone who shares one’s love of learning. Mencius, Confucius’ most famous successor, lists friendship as one of the celebrated Five Relations, making it of the most valuable social relations next to family ties.

For Aristotle, friendship is one of the most important virtues in achieving the goal of eudaimonia (happiness). While there are different kinds of friendship, the highest is one that is based on virtue (arête). This type of friendship is based on a person wishing the best for their friends regardless of utility or pleasure. Aristotle calls it a “…complete sort of friendship between people who are good and alike in virtue…” This type of friendship is long lasting and tough to obtain because these types of people are hard to come by and it takes a lot of work to have a completely virtuous friendship. Aristotle notes that one cannot have a large number of friends because of the amount of time and care that a virtuous friendship requires. Aristotle values friendship so highly that he argues friendship supersedes justice and honor. First of all, friendship seems to be most valued by people, so much so that no one would choose to live without friends. People who value honor will likely seek out either flattery or those who have more power than they do, in order that they may gain through these relationships. Aristotle believes that love is greater than this because it can be enjoyed as it is. “Being loved, however, people enjoy for its own sake, and for this reason it would seem it is something better than being honored and that friendship is chosen for its own sake.” The emphasis on enjoyment here is noteworthy: a virtuous friendship is one that is most enjoyable since it combines pleasure and virtue together, thus fulfilling our emotional and intellectual natures.

Our Related Articles

To discover further insights into the habits of happy individuals, you may want to read our following articles.